This website has some useful resources to be a little more greener.

This website has some useful resources to be a little more greener.

Tuesday 29 January 2008

Friday 25 January 2008

Andrew Hartley's book

Andrew Hartley's book Christian and Humanist Foundations for Statistical Inference: Religious Control of Statistical Paradigms is now out published by Wipf and Stock. Details are available here.

Andrew Hartley's book Christian and Humanist Foundations for Statistical Inference: Religious Control of Statistical Paradigms is now out published by Wipf and Stock. Details are available here.

Thursday 24 January 2008

B J van der Walt: Transformed Ch 3

The title chapter as it were began life as a paper delivered at the International Conference of IAPCHE at Dordt College, Iowa in 2000. The subtitle 'The challenges of Christian higher education on the African continent in the twenty-first century' ably summarises the chapter. Van der Walt tackles them in reverse order.

The situation on the African continent is first described. This makes sobering reading. Export of manufactured goods is virtually zero. In the sub Sahara there are 12 telephones per 1000 people. 184 million have no access to water. 184 million have no access to safe drinking water. I could go on ...

Romans 12:1-2 is then examined as a starting point for a basic vision. "It is a clarion call for the transformation of the whole of life' (p. 114). It contains a warning, a command and a promise.

The warning regards the secularisation of the world; our response should be transformation of, not isolation from or conformity with, culture.

The command indicates where we are to start. The whole body is to be presented as a living sacrifice and our minds are to be renewed. The use of the imperfect tense in Rom 12:1,2 'indicates that God requires an on-going, continuos reformation. If we don't reform, we will conform to the deformation of the world' (p. 113).

The promise is that we will approve, accept God's will.

Van der Walt then outlines ten excellent criteria for transformational scholarship; it should be:- visionary

- integral

- rigorous

- critical

- open

- relevant

- culturally sensitive

- communal

- global

- modest

He concludes this chapter with a proposal for the establishment of an African Centre for Christian Higher Education.

Wednesday 23 January 2008

Tuesday 22 January 2008

Jon Swales switches

Powered by ScribeFire.

Monday 21 January 2008

Defending God's earth

Environmental issues are rarely out of the public eye. One that has caught the press attention recently is the Newbury bypass. The anti-bypass campaign has become a focus for civil rights as well as for environmental issues. There have been 720 arrests and it has cost the Highways Agency around £1.5 million in security.

However, compared with the States the campaign seems rather tame. There environmental groups are prepared to die and even kill in "defence of mother earth". Their motto is "Earth First!" They engage in ecoterrorism such as spiking trees, sabotaging roads, dismantling helicopters and destroying bulldozers. For them the real terrorists are the polluters and desecrators of nature.

All this raises important questions for Christians. Should we be involved in environmental action? If so, how far should we go? Should we be involved in civil disobedience?

Some Christians would say that we should not be involved in environmental care. Many reasons are given, but as we peel them back they seem to be no more than excuses:

Excuses for non-involvement

The problems are far too complex and too enormous for me to make a difference.

The size of the problems are irrelevant. We are not necessarily called to make a difference; God calls us to be faithful to him. He will look after the results.

"Going green" means being part of the New Age movement.

This is no more true than going door-knocking means being a Jehovah's Witness. New Agers do not have to have the monopoly on environmental care - after all the earth is the Lord's.

Jesus didn't get involved in environmental issues, so neither should we.

Jesus never wore trousers, does that mean we don't have to? Jesus was a person of his time; the environmental problems that we face today were not a major problem 2000 years ago in rural Palestine. Were he born in our time he would certainly have had things to say. He did get involved in his Father's world - his incarnation and resurrection are testimonies to that.

The Earth will get worse and worse there is nothing we can do about it, until Jesus returns and creates a new earth.

Such end-time fatalism is not supported by a careful reading of the Scriptures. The fate of the earth is not destruction but rather transformation. There will be a continuity between this earth and the new earth, in the same way as there is a continuity between our present bodies and our resurrected ones.

A Biblical Framework for Environmental Care

For Christians the guiding principles must be those of the Scriptures. The problem is that there are no obvious chapters or verses to quote. We need to discern the whole direction and tenor of the Scriptures. One way of doing this is to use the framework of creation, fall and redemption.

Creation

The Bible declares unambiguously: "The Earth is the Lord's" (Ps 24:1). It is this concept that is basic to a Christian environmental ethic. It is God's world: he created it, he loves and cares for it.

God commissioned humans, as his image bearers, to rule and subdue the earth. The language of subduing and ruling is very strong, in one place subdue is translated as rape (Esther 7:8). The meaning of these words must, however, be understood from their context. Subduing and ruling are to be done as image bearers of God, he is our role model: it is thus less exploitation and more specifically leadership as servanthood. It is God's earth, it is not ours to do with it as we see fit: we are stewards, as such we are accountable to God for our treatment of it. We are to serve the creation so that it can develop as God intends it. This involves caring and defending the earth as well as developing and cultivating it.

Fall

But then came sin. The first sin in some way affected the whole of creation. All environmental disasters can be traced back to the fall and to sin. Thus our stewardship becomes all the more difficult, it becomes a painful toil (Gen 3:16).

Human struggle with the earth is taken up in subsequent chapters in Genesis. Cain's murder of his brother means that the ground will no longer yield its crop (Gen 4:10-14). The prophet Hosea takes up the same theme: sin results in the land mourning (Hosea 4: 1-3).

Redemption

However, the fall is not the end. God, the author, enters his own story. Throughout the Old Testament we have in the flood story and in the Jubilee legislation glimpses of God working to redeem his creation. But it is ultimately in Jesus that redemption is accomplished.

Jesus' work on the cross redeemed the whole of creation. Nothing is exempt from the reconciling power of the cross. There is the potential of reconciliation for all of creation (Col 1:20). The work that Jesus began on the cross he will finish when he returns. The fate of the earth will not be one of destruction but of renewal, of transformation.

How far should we go?

Thus there seems to be a strong biblical basis for environmental care, it is part of our calling as stewards. God cares for it and so should we. But how far should we go in defence of God's earth?

1. Put our own house in order.

How can we live more benignly upon the earth? Recycle, reuse and repair where possible; and consume less. When tempted to consume ask yourself:

- Do I really need it?

- Why do I want it?

- Is it produced with just principles?

- How does it affect the environment:

- in the way it will be used and in the way it was produced?

- Will it promote responsible stewardship?

2. Get your local Church involved.

Consider joining with others to study what the scriptures say on environmental issues, pray, compile lists of resources, start a recycling scheme or encourage people to use it if one is already available.

3. Look broader

Educate yourself: but don't believe all that you see or read, every organisation has some axe to grind.

Use your democratic rights: vote in local and general elections, take up specific issues and lobby local government and MPs. The postage stamp is a powerful weapon.

Civil disobedience?

The Newbury anti-bypass campaign, involved many people in civil disobedience. Is this an option for Christians? Many point to Romans chapter 13 as demanding unconditional obedience to government. Government is established by God to be God's servant, to do justice (Rom 13: 1-5). And yet we are not called to blind obedience. Government is to be a servant, when it tries to become an oppressive master (e.g. Rev 13) we cannot obey. Without civil disobedience by Hebrew midwives Moses would have died at birth, and in many countries the gospel would not be preached. Civil disobedience for the Christian consists in obeying God rather than human authority (Acts 5: 29).

A Christian then can engage in civil disobedience, but there are also God-given constraints. It should be: a last resort; non-violent (harming neither people or animals, and property only minimally); an opposition of policies, not people; and done fully realising and accepting the consequences; arising from it.

Hence, involvement in campaigns such as the Newbury bypass are not off limits for Christians, but we cannot always accept our cobelligerents' worldview (see table) and sometimes our policies would drastically diverge. Involvement must arise out of a commitment to the lordship of Christ over his earth and not from selfish reasons.

Getting to the roots

For the Christian the root of all environmental problems is the fall, most can be traced back to greed and idolatry. Without tackling that problem we will, to an extent, be fighting a rear-guard action. Nevertheless, the defence of God's earth is part of our responsibility as stewards; but it is God first rather than earth first.

Sunday 20 January 2008

Everything is spiritual

At last someone else has taken up the neo-calvinist message: 'all of life is religion'.

[HT Jon Swales]

The theological ramblings of an Anglican ordinand

Update: he's now blogging here

Odds and sods

Vote on the image of God!

Paul Helm on 'Saving the planet'

American Theological Inquiry - a new online journal [HT Faith and Theology]

Four types of emergent churches and thinkers

Groothius's review of The God Delusion

Hector Avalos, author of The End of Biblical Studies (Prometheus 2007), responds to J P Holding on Debunking Christianity

Powered by ScribeFire.

The four horsemen

Hour 1 - Google Video | Quicktime (78.7 MB) | Torrent | Audio Only (mp3, 26.6 MB)

Hour 2 - Google Video | Quicktime (73.6 MB) | Torrent | Audio Only (mp3, 27.1 MB)

Saturday 19 January 2008

Andrew Basden pages

I am pleased to announce the launch of the Andrew Basden pages on All of life redeemed. Andrew is Professor of Human Factors and Philosophy in Information Systems at the Salford Business School, at the University of Salford he also maintains the invaluable Dooyeweerd pages. He is the author of A Philosophical Framework for Understanding Information Systems. There are 16 papers of Andrew's available in html form:

1999. On the ontological status of virtual environments

1999. A new framework for sustainability

2001. Beyond emancipation

2001. A philosophical underpinning for IT evaluation

2002.The critical theory of Herman Dooyeweerd?

2002. A Philosophical Underpinning For ISD

2003. with A. Trevor Wood-Harper A Philosophical Enrichment of CATWOE

2003.Enriching critical theory

2003.Levels of guidance

2004. Emancipation as if it mattered

2004. On Appealing to Philosophy in Information Systems

2005. Enriching humanist thought

2006. Information systems as a life-world

2007. 'Fresh light thrown on the Chinese room'

2007. A brief overview of Dooyeweerd's philosophy

2007. Frameworks for understanding IS and ICT

Friday 18 January 2008

Wednesday 16 January 2008

Cambridge Saturday School of Theology

The course will include the following lecture topics and much more:

- Introduction to thinking about Philosophy in a Christian way (Rampelt)

- The rise of Naturalism and Skepticism (Rampelt)

- Dawinism in the past and present (Rampelt)

- From scientific control to the manipulation of society (J. Chaplin)

- The rise of modern Liberalism and the responses of Socialism and Romanticism (J. Chaplin)

- Political Ideologies Today (or anti-ideologies): Capitalism, Multiculturalism, Islamism, etc.(J. Chaplin)

- Art and its place in a biblcal worldview (A. Chaplin)

- Christianity's relationship to artistic making: a history and theology (A. Chaplin)

- Jesus-centred viewing and listening: The Christian and the contemporary arts (A.Chaplin)

Details When? The second Saturday of every month Tyndale House, Hexagon Room, 36 Selwyn Gardens, Cambridge, CB3 9BA click HERE for map How to Apply

Where?

Monday 14 January 2008

B J van der Walt: Transformed Ch 2

This is a paper delivered at the International Symposium of the Society for the Reformational Philosophy on Cultures and Christianity AD 2000 held at Hoeven, the Netherlands, 21-25 August 2000. A shorter version without reference to development was published as part of the conference proceedings in Philosophia Reformata 66 (1) (2002)23-38, with the subtitle 'A perspective from the African Continent'. An edited version also appeared in African Journal for Transformational Scholarship 1 (1) (Nov 2002) 1-26.

Here van der Walt starts and ends by briefly looking at development. The origin of the idea is Western and the word development was first mentioned in 1944; this had the effect of splitting the world into two: the developed and the undeveloped. He also itemises some of the dubious motives behind development. The zeal behind development can only be understood when we see it as 'a secular form of salvation' (p. 47). He then turns to the concept of 'culture'. He examines two definitions of culture: the segmental and the comprehensive. The first sees culture as something that bestows 'lustre upon life'; the second regards it as 'human life in its totality' (p 49). He rightly asserts that 'every human being is a cultural being'. Development he notes is a cultural product. Each culture has aspects that are good, but also each culture has its own blindspots; each culture has a mixed nature.Using a diagram of five concentric circles he examines five aspects of culture. The inner circle is the religious dimension, the next the worldviewish dimension, followed by the social, the material or technical and then the behavioural dimensions. As with all models it has limitations, but t serves well to illustrate the relationship between religion, worldview and culture: 'Religion and worldview influence (the remainder of) culture, but culture (for instance socio-economic-political circumstances) also influences worldview and religion' (p. 53). Religion he defines as 'the cultural directedness of all human life towards the real or presumed ultimate source (God/god) of meaning and authority'.

Worldview - our perspective on created reality - next comes under scrutiny. He makes an excellent observation on the difference between a worldview and an ideology: '' a wolrdview and an ideology have the same structure, but different directions. A worldview is normal and healthy; an ideology can be dangerous' (p. 58) Any worldview can degenerate into an ideology. He identifies six aspects of a worldview:

1. God/god

2. norms or values

3. being human

4. society or community

5. nature

6. time and history

Two of possible options between Christianity and culture, conformity and isolation, are dismissed in favour of a reformation or transfromation of culture. Our culture task, then, is to serve God (the direction) according to his will (the normative) in his creation (the structural) (p.62).

The six aspects of a worldview are identified in the Western, African and Christan worldviews. These are summarised in this table:

He then concludes by offering a definition of development:

Development is the (1) balanced unfolding of (2) all the abilities of the human being and (3) the potential of material things, plants and animals (4) according to God's purpose and (5) His will, to enable the human being (6) within his/ her own culture, (7) to fulfil his/ her calling (8) as a responsible steward of creation (9) in a free society (10) to the honour and glory of God.

Saturday 12 January 2008

Real Science, Real Faith

- Entire book (pdf, 674 KB)

- Contents (pdf)

- Surprised by Science Colin Russell, Chemist and Historian of Science (pdf)

- Down to Earth Martin Bott, Geologist (pdf)

- Credibility and Credo Roy Peacock, Engineer (pdf)

- A God Big Enough John Houghton, Meteorologist (pdf)

- A Talent for Science Ghillean Prance, Botanist (pdf)

- Non in tempore sed cum tempore Robert Boyd, Space scientist (pdf)

- Biology and Belief Andrew Miller, Molecular biologist (pdf)

- How can I know God, or rather be known by God? Duncan Vere, Physician (pdf)

- Can Science and Christianity Both Be True? Colin Humphreys, Materials scientist (pdf)

- Personal Faith and Commitment Elizabeth Rhodes, Chemical engineer (pdf)

- Pathways Roger Bolton, Industrial chemist (pdf)

- Brains, Mind and Faith Malcolm Jeeves, Psychologist (pdf)

- Man–Dust with a Destiny Monty Barker, Psychiatrist (pdf)

- To Whale or not to Whale, That is the Question Ray Gambell, Conservation biologist (pdf)

- Genes, Genesis and Greens Sam Berry, Evolutionary biologist (pdf)

- Science and Christian Faith Today Donald MacKay, Physicist and brain scientist (pdf)

- Bibliography (pdf)

A Fox in sheep's clothing?

Matthew Fox's Creation-Centred Spirituality

Matthew Fox's Creation-Centred SpiritualityWestern Christianity, because of its emphasis on dominion, has often been charged with paving the way for the current environmental crisis, consequently theologians and writers have attempted to defend Christianity against this unjust accusation. One such attempt is what has been named "creation-centred spirituality". Matthew Fox, an American Dominican priest and theologian, is the foremost representative of this recently developed spirituality. His basic premise is that we need a new religious paradigm: one that replaces the old dualistic and patriarchal "exclusively fall/redemption spirituality"; that seeks to place humanity within the creation; that celebrates creation's beauty and our creativity; that affirms our bodies. A creation-centred spirituality, Fox believes, is one such appropriate paradigm.

Fox's writings on "creation-centred spirituality" include Original Blessing ,[1] The Coming of the Cosmic Christ [2] and Creation Spirituality[3]; these have been influential among Catholics and Protestants alike, and further afield. He appeals to Christians who are seeking a spirituality that affirms rather than denies the creation, because he uses theological terms and is theologically literate. He also appeals to some greens who are searching for a spirituality to explain the principles of human awareness and existence and interconnectedness. Creation-centred spirituality, because it has roots in a wide range of spiritual traditions and religions, resonates with others of different cultures and beliefs. Fox has been accused of "pure Taoism" and of being "aboriginal"; his is the ultimate ecumenicalism!

So is his creation-centred spirituality benign? Is it as he claims orthodox and supported by the Bible?

A silenced prophet?

Despite his popularity not everyone is happy with Fox's teachings. In December 1988 he was silenced by his Dominican Order for one year; ironically this had the effect of increasing his popularity. A panel was set up to examine his work, and came to the conclusion that he was not heretical. Commenting on this, Fox says:

I have done my homework and have proven that what I am saying is part of the mystical Christian tradition.[4]

In 1994 Fox was dismissed from his order and became an Episcopal priest. It is important to Fox that his teachings are seen as part of the Christian tradition: he thinks tradition distinguishes a spirituality from a cult.

He has never sought confrontation with the Vatican, but that does not mean the Vatican is totally happy with Fox's work. In an interview with Satish Kumar, the editor of Resurgence, Fox remarks:

I have always written for the people [as opposed to the Vatican], and tried to speak to the people, and that is what I will continue doing, and if it means that I will be expelled from the priesthood, then that is the price I will have to pay. I will not leave the priesthood voluntarily because I have spent twenty years proving that this is our tradition; it is in the Bible, it is our mystic tradition.[5]

The mystic tradition

This "mystic tradition" which Fox sees as part of the Christian heritage, however, involves a highly selective view of Christian history on his part. In particular he draws on the "Rhineland mystics", who he sees as "champions of an ecological spiritual consciousness";[6] these include Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), Mechtild of Magdburg (1210-1290), Meister Eckhart (c.1260-1327) and Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1415). Technically the latter is not a "Rhineland mystic" but Fox feels she deserves to be called one. He makes use of the works of Francis of Assisi (1181-1225) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274).[7]

However, Fox's handling of these mystics is not always fair. Simon Tugwell O. P., in a review of Fox's Breakthrough [8] a translation of and commentary on Eckhart, observes:

it is difficult to avoid the feeling that the mistranslation is deliberate, intended to minimise anything that would interfere with the alleged "creation-centredness" of Eckhart's spirituality.[9]

Tugwell also notes that Fox

repeatedly insults his readers with bland assertions which it would be very difficult to substantiate, with tendentious half-truths, or with downright falsehood.[10]And concludes that "Breakthrough seriously misrepresents Eckhart".

Creation-centred spirituality

Fox's creation-centred spirituality, which "considers the environment to be a divine womb, holy, worthy of reverence and respect"[11], is a backlash to what he sees as the poverty of Western spirituality. Fox is opposed to the subject/object dualisms that have dominated theology, at least according to Fox, since Augustine;[12] and he rejects the emphasis - again through Augustine - on a fall/redemption theology.[13] It will be worth looking at both these in turn. Before doing so a brief comment on Fox's use of Augustine is called for.

Augustine (354-430)

The blame for our current spiritual poverty is laid, almost solely, at Augustine's door:

The creation-centred spiritual tradition offers an alternative to much of Christian history for it delineates the truth that hellenism and its dualisms regarding the body, feeling and spirit is not Jewish or Biblical thinking and that Augustine's dualistic interpretation of Christianity was a distortion of Jesus' spirituality. since vast proportions of both Catholic and Protestant churchlife and polity have been constructed on Augustine's dualistic Neoplatonic world view, spirituality in the West must let go of Augustine's thought if it is to immerse itself in the profound wellsprings of Biblical spirituality and contribute to creating a global civilisation.[14]Lawrence Osborn points out the irony of Fox's vehement attack on Augustine. Fox "relies heavily upon the mystical tradition of his own religious order: a mysticism which is steeped in Augustinian influence".[15] It is this selectivity of the truth that characterises much of Fox's scholarship; this is not to say it is deliberate: Fox's world-view - as does everyone's - colours his perception of reality and his choice of "facts".

Dualism

Fox is only partly correct when he notes that "Subject/ object dualisms have characterized the mainstream of spirituality in the West from St. Augustine to Jerry Falwell and points in between".[16] Dualism was also rife pre-Augustine: Plato (427-347 BC) had a form/ matter dualism that characterised all his philosophy, which in turn had an enormous impact on the early church fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215), Origen (c. 185-254) and Basil of Caesarea (c.330-79). It was through Augustine, under the influence of Plotinus, that dualism "received its ultimate theological legitimation".[17] However, the mystics that Fox draws upon were not free from dualism. Aquinas in particular was responsible for a nature/ grace dualism that paved the way for Descartes' radical dualism of mind/ matter.[18] This mind/ matter dualism is the root of the desanctification of nature,[19] the very thing Fox wants to avoid!

Fox is so keen to eradicate any dualism that he obliterates any distinction between the Creator and his creation. This distinction is described by Fox as "the ultimate dualism".[20] To do this he does not embrace pantheism (God is everything and everything is God) but the closely related panentheism (God is in everything and everything is in God).

...we have to move from theism to panentheism. Theism has haunted us for 300 or 400 years in the West and it basically says I'm here and God is somewhere else, and prayer is about getting to God or getting God here. This encourages subject/ object relationships. Carl Jung said that there are two ways to loose your soul and one is to worship a god outside of you.[21]

For some theologians panentheism can be a subset of theism; for Fox it is more a subset of pantheism:

I am proposing a new theology of creation in which God is not an absentee landlord. God is the creation.[22]He is vehemently opposed to what he calls "theism": "... theism is by definition dualistic".[23] In 2005 – when Ratzinger was made Pope - he posted 95 theses to the ‘door’ of St Joan’s, MN.

Thesis 6 was:

Thesis 6 was:Theism (the idea that God is ‘out there’ or above and beyond the universe) is false. All things are in God and God is in all things (panentheism).However, his use of the term theism is a misleading. Most of his criticisms of theism apply to deism but not to theism.[24] He regards theism as naive compared with panentheism:

Moving from a theistic ("God out there" or even "God in here") to a panentheistic theology ("all is in God and God is in all") is a requisite for growing up spiritually.... A theistic imaging of God is essentially adolescent for it is based on an ego mind-set, a zeroing in on how we are separate from God.[25]In attempting to undermine this "dualism" he falls into the trap of monism: all is one. Fox's panentheism is an attempt to do justice to the involvement of God in his creation and to undermine any desanctification of creation. It fails because it does not distinguish God from his creation: it deifies the creation; consequently humanity becomes divine and paradoxically no different to the grass. A more biblical way to deal with the problem of God's involvement with creation is through the traditional theistic categories of transcendence and immanence. The few Bible verses that Fox cites (out of context) for panentheism offer no support (Luke 17:21; John 15:5; Acts 17:25).[26]

Fall/redemption theology

We can now turn to Fox's trenchant criticism of what he calls fall/ redemption theology. Fox hopes to replace this with a creation-centred theology. Any attempt to mzrginalise the fall is immediately confronted by the problem of how to explain evil, death and imperfection. For Fox, death is a natural event and imperfection is integral to creation. Further, in rejecting a fall/ redemption theology, he bypasses the cross as the means of reconciliation. The cross is seen as a symbol of "letting go".[27] This reduction of the the cross is (at best) sub-Christian. Fox, in bypassing the redemptive function of the cross, ceases to offer a Christian spirituality and does not remain within the Christian tradition.

In discussing the "fall/ redemption" tradition Fox shows misunderstandings and commits several errors. The following factors undermine his position.

(i) His phrase the "fall/ redemption" tradition is a misnomer; it is best characterised by the term "creation, fall and redemption". For obvious reasons Fox ignores the first part.

(ii) His claim that the "fall/ redemption" tradition does not have an appreciation of, or theology of[28], creation [29] is misfounded. The "philosemitic medievalist" Margaret Brearley shows that in the Middle Ages when the fall/ redemption theology was perhaps at its peak that these theologians had an "intense preoccupation" with the creation. She cites Wolfram von Esschenbach, George Herbert and Bousset as medieval examples of those within the fall/ redemption tradition who could write in praise of creation.[30]

(iii) Even today theologians and writers within this tradition are expounding an ecologically aware theology; examples are Loren Wilkinson,[31] Wesley Granberg-Michaelson [32],Rowland Moss[33], Calvin DeWitt and Steven Bouma-Preideger.

Other problems

There are several other aspects of Fox's position that give cause for concern. Briefly these include: his defective anthropology - we are divine and have a responsibility to "divinize the universe";[34] his acceptance of non-Christian traditions such as Taoist, Kabir (Hindu/Sufi), Native American, Wicca (Starhawk, a well known white witch, teaches at his Institute in Culture and Creation Spirituality), African, Zen, Celtic and Hasidic;[35] his understanding that the basis of all sin is dualism [36] - he also names dualism as "original sin";[37] his concept of salvation as "awakening to our divinity";[38] and his desire to see an emerging global civilisation that is "grounded on the understanding that the world is an undivided whole",[39]"a Global Civilisation which will usher in a new era in the divinization of the cosmos".[40]

Conclusion

What then are we to make of Matthew Fox? There are many aspects of his work we can endorse, even if we do not go the whole way, these include his rejection of dualism, his attempt to develop a world-affirming rather than world-denying spirituality and his desire to be equally inclusive of female and male; at least now these crucial issues are on the theological agenda. His increasing popularity and apparently uncritical acceptance by many Christians, however, can only be cause for concern. In this article I have attempted to show that Fox stands outside orthodox Christianity - be it Catholic or Protestant - despite his vociferous claims to the contrary. The methods and sources he uses to support his case are at best "suspect".[41]

I can only conclude with Lawrence Osborn [14] and Margret Brearley [29] that Fox's teachings are a vehicle for highly dubious New Age thinking; they are New Age in Christian clothing.

Notes

1 Original Blessing: A Primer in Creation Spirituality (Bear & Co, 1983; UK edn 1990).

2 The Coming of the Cosmic Christ (Harper & Row, 1988).

3 Creation Spirituality: Liberating Gifts for the People's of the Earth (HarperSanFrancisco, 1991).

4 "From original sin to original blessing" Resurgence Jan/ Feb 1991 (issue 144) p. 26.

5 Ibid.

6 "Creation-centered spirituality from Hildegard of Bingen to Julian of Norwich: 300 years of an ecological spirituality in the west" Cry of the Environment: Rebuilding the Creation Tradition ed. Philip N. Joranson and Ken Butigan (Bear & Co, 1984) ch. 4.

7 For a more comprehensive list of those he believes "lived out and taught the creation-centered tradition" is to be found in "Appendix A: Toward a Family Tree of Creation-Centered Spirituality" Original Blessing pp 307-15.

8 New Blackfriars vol. 63 (1984) pp. 195-7.

9 Ibid p. 197.

10 Ibid p. 196.

11 Cry of the Environment p. 84.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Matthew Fox and Brian Swimme Manifesto for a Global Civilization (Bear & Co, 1982) pp. 17-8.

15 Meeting God in Creation Grove spirituality series No 32 (Grove Books, 1990).

16 Cry of the Environment p. 84.

17 Brian J. Walsh and J. Richard Middleton The Transforming Vision: Shaping a Christian World View (IVP,1984) ch. 7.

18 Philip Sherrard The Rape of Man & Nature: An Enquiry into the Origins and Consequences of Modern Science (Goolgonooza Press, 1987) p. 60.

19 Ibid.

20 Original Blessing p. 89.

21 Resurgence p. 24. See also Original Blessing pp. 89ff.

22 Resurgence p. 24.

23 Cry of the Environment p. 86.

24 He even refers to a "Newtonian theism that posited a clockmaker God who wound the universe up and sat back...". An excellent description of deism not theism! Original Blessing p. 90.

25 Cry of the Environment. p.97.

26 Resurgence p. 24.

27 Original Blessing p. 166.

28 This is the same accusation made by Sean McDonagh: "This theological tradition has no adequate theology of creation" To Care for the Earth: A Call to a New Theology (Geoffrey Chapman, 1986) p. 81.

29 Margret Brearley "Matthew Fox: creation spirituality for the aquarian age" Christian Jewish Relations vol. 22 (2) (1989) p. 40.

30 Ibid. p. 41.

31 Editor of Earthkeeping: Christian Stewardship of Natural Resources (Eerdmans, 1988).

32 A Worldly Spirituality: The Call to Redeem Life on Earth (Harper & Row,1984) and Ecology and Life: Accepting Our Environmental Responsibility (Word, 1988).

33 The Earth in Our Hands (IVP,1982).

34 Manifesto p. 19.

35 These are all included in his "family tree of creation-centered spirituality" Original Blessing Appendix A pp. 307-15.

36 Original Blessing p. 296.

37 Cry of the Environment p. 88.

38 Ibid p. 235.

39 Manifesto p. 13.

40 ibid p. 7.

41 This is the conclusion of Oliver Davies "Eckhart and Fox" Tablet vol. 243 August 1989 pp. 890-1 (cited in Brearley op. cit.).

Wednesday 9 January 2008

B J van der Walt Transformed Chapter 1

One of the largest problems facing Christians who want to develop and embrace a biblical worldview is dualism. Dualism is the tendency to split life into two levels: a higher and a lower sphere. Examples might be sacred and profane, spiritual and secular or grace and nature.

Van der Walt aptly describes it:

Turning next to the tendencies in African Christianity he briefly looks at Kwame Bediako's analysis and the similarities between African theologians and the early church theologians. He finds Bedakio's approach, among other things, lacks an understanding of the 'dangerous ontological dualism inherent in the theologies of early christians' (p. 18). One major tragedy he identifies within Africa Christianity is its escapist tendency, this he believes is a consequent of the truncated and domesticated message of the missionaries. Among their many characteristics are pietism, individualism, an emphasis on personal holiness only, the spiritualising of the kingdom of God and the reluctance to be involved in politics. Together with an escapist mentality comes an increasing secularisation.

Van der Walt's vision for South Africa, which he has spelled out in a number of other books, is that it will be liberated from the shackles of dualism and includes 'an interal, radical (socially) involved and kingdom Christianity' (p. 23).

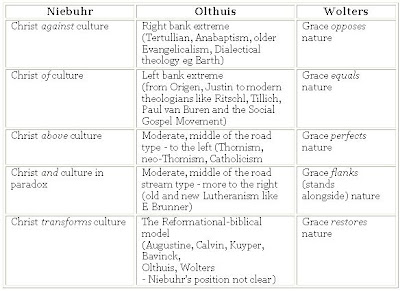

He now moves on to look at typology of five dualisms and to give a biblical critique of them. As I have mentioned bfore any mention of Christianity and culture will almost certainly invoke Niebhur - and this chapter is no different. He compares Niebhur's approach with James Olthuis's and Al Wolters's. This is neatly summarised in a table:

He then looks at how these positions might view politics and how they might respond to the question 'Should I go to a rock concert?'. The responses might be:

1. Stay away - it is from the devil!

2. If it is a good performance no problem - go for it.

3. You may attend - but remember before and after to confess your sin.

4. Please go - but I want to see you in church on Sunday.

5. Be careful! First ask yourself whether it will be possible to serve God - not before or after the event, but in your attendance.

He then examines these two-realm dualisms from a biblical perspective. He warns us to be on the look out for unbiblical terminology that may reveal a dualistic tendency. These include nature/ grace; nature/ supernature; secular/ religious; natural (general) revelation/ supernatural (special) revelation; profane/ secular; and so on.

Along the way he looks at the misconception of equating the church with the kingdom: 'the church reveals the kingdom but it is only one expression' (p. 34). He makes a distinction between religion and faith: faith is one of the modes of being religious, religion is not an addition but the essence of life.He makes an excellent point about two-realm theories: they arise from different viewpoints as to the place in creation that sin is located, how serious the effects of sin are and how great or little the need for redemption will be (p. 36). He also draws out the different meaning of dualism in Dooyeweerd and Vollenhoven. For Dooyeweerd dualism is primarily of a religious-worldviewish nature; the antithesis is given an ontological status. In Vollenhoven, dualism is used in the sense of being the opposite of monism: monists have to explain the variety in creation, whereas dualists have to explain the unity of reality.

He concludes by offering a brief description of a reformational worldview. It is free from dualism(s), it is integral and holistic.

Tuesday 8 January 2008

Monday 7 January 2008

The Terry Lectures on-line

Alvin Plantinga "Science and Religion: Why Does the Debate Continue?"

Ronald L. Numbers "Aggressors, Victims, and Peacemakers: Historical Actors in the Drama of Science and Religion"

Bas C. Van Frassen "The empirical stance" available from here.

The most popular posts of the last year

1. The link for the audio of the Lennox-Dawkins debate

2. The Dawkins links

3. The anthroposophical worldview - even though it was written more than a year ago

4. Calvin Seerveld

5. Review of Frank Viola's Pagan Christianity

6. A Christian view of work

7. Dawkins's article in Private Eye

Powered by ScribeFire.

Sunday 6 January 2008

Theo Plantinga: on-line resources

- Christian Philosophy Within Biblical Bounds (Inheritance Publications, Alberta, 1991)

- Contending for the Faith: Heresy and Apologetics (Paideia Press, Jordan Station, 1984)

There are a number of his papers; including:

- Christianity and Visualism

- The Christian Philosophy of H. Evan Runner

- Commitment and Historical Understanding: A Critique of Dilthey

- Creation, Revelation and Novelty

- Dilthey's Philosophy of the History of Philosophy

- Protestantism and Progress

- The Real Meaning of Kant

- Where Would We Be Without Punishment?

An index of the files is here.

Saturday 5 January 2008

B J van der walt: Transformed by the Renewing of Your Mind

Transformed By the Renewing of Your Mind

Transformed By the Renewing of Your Mind Shaping a biblical worldview and a Christian perspective on scholarship

B J van der Walt

The Institute for Contemporary Christianity in Africa, Potchesfstroom, 2001 (third print 2007)

ISBN-10: 1868223825

ISBN-13: 9781868223824

198pages; pbk

As the subtitle suggests this book examines two concepts: a Christian worldview and Christian scholarship, particularly that in higher education. The context is Africa, but the principles apply anywhere in the world. Bennie van der Walt is well equipped to tackle these subjects. Until his retirement in 1999 he lectured at the Potchesfstroom university in South Africa and was the founder and director of the Institute for Reformational Studies. He has also been highly involved with IAPCHE (International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education). Several of the chapters in this book were originally lectures presented at IAPCHE events.

The six chapters are:

2. Culture, worldview and religion

3. Transformed by the renewing of your mind

4. Taking captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ

5. The pilgrim's progress of a Christian academic

6. Our past heritage, present opportunity and future challenge.

A brief overview

The main thesis of the book is that we urgently need a genuine, biblical worldview and this should be seen in Christian scholarship and education. The first chapter looks at one of the major obstacles in forming a biblical worldview: dualism. The second looks at the relationship between the key concepts of worldview, culture and religion and this is applied to the important, particularly in the African context of development. The subsequent chapters start to focus on the need for a Christian worldview in higher education. Chapter 3 looks at what it means to renew the mind in the cotext of higher education and in general and in Africa in particular. Chapter 4 looks at the challenegs post 2000. The theory of these chapters is then applied in the story of Thomas, an African Christian academic. His struggle to integrate his scholarship with his Christianity as he moved from being a Christian and then a scholar to become a Christian scholar are told. The final chapter is a look back and forward to the work of the IAPCHE.

I will look at these chapters in more detail in subsequent posts.

The book can be obtained directly from the author; details are here.

(Re)thinking worldview 12

… in every tradition, every denomination, every church and every believer. … A youth pastor can pierce his tongue and host a skateboarding event for the community, calling it engagement, when in fact it looks more like assimilation’ (p 230).He then turns to the role of imagination in the ‘creative’ arts. He makes some excellent observations on Christians and the imaginative endeavour, be it in art or in fiction writing. He explores two important questions: ‘ is the Christian imagination creative or didactic? … what is the anatomy of the Christian imagination’ (p. 234).

This is an excellent chapter and really deserves to be expanded in a book. It would be a great service to all, and not just Christian, artists. With particular regard to Christian imagination he makes – and expands upon – four points:

1. Christian imagination is an image bearer’s echo of the Creator

2. Christian imagination embodies the biblical worldview.

3. Christian imagination is incarnational.

4. Christian imagination aspires towards excellence.

These points could also apply to any other creational activity.

Friday 4 January 2008

(Re)thinking worldview 11

He cites a wonderful quote of Binx Bolling from Walker Percey’s novel The Moviegoers – judging from the quote seems like an excellent book to check out:

My unbelief was invincible from the beginning. I could never make head or tail of God. The proofs of God’s existence may have been true for all I know, but it didn’t make the slightest difference. If God himself had appeared to me, it would have changed nothing. In fact, I have only to hear the word of God and a curtain comes down in my head.

Bertrand draws upon the insights in this quote and makes four excellent points, which he examines:

1. Unbelief treats God as the enigma

2. Unbelief is a faith commitment

3. Unbelief will not accept proof

4. Unbelief is a spiritual, not an intellectual condition.

Tuesday 1 January 2008

AoLR update

Two more of Roy Clouser's papers have been added:

1985. Dooyeweerd on religion and faith: a response. ICS Conference paper.

A response to James Olthuis's chapter in C T McIntire (ed.). 1985b.The Legacy of Herman Dooyeweerd: Reflections on Critical Philosophy in the Christian Tradition. University Press of America: Toronto.

1981. Four Options in the Philosophy of Religion. Anakainosis (Toronto) April.

And thanks to the permission of the Churchman - the journal of the Church Society a paper by Stacey Hebden Taylor:

'The Reformation and the development of modern science'. Churchman vol 82 (2) (1968): 87-103.

(Re)thinking worldview 10

Bertrand makes an interesting observation: ‘apologetics is the task of giving unbelievers a way to justify what the Spirit is doing in their hearts’ (p 201). If this is so then it may well mean that apologetics could have a place in ‘persuading’ the unbeliever.

Odds and sods

Reformational Publishing Project has made available a pdf of S U Zuidema's 1972. 'Common grace and Christian action in Abraham Kuyper' from Communication and Confrontation. Toronto: Wedge. pp 52-105.