The sceptre of creation and evolution will haunt every book on science and religion; so, it is inevitable that Dowe deals with it in this the longest chapter of the book.

In this chapter Dowe looks at the nature of teleological explanations, Paley’s design argument, Darwin’s natural selection and his views about God, Asa Gray and the modern creation science movement.

He starts by looking at Aristotle and Aquinas’s notion of teleology. Aquinas takes Aristotle’s view of teleology – everything has a purpose – and turns it into a design argument: things have purpose because they are designed by God. Aquinas’s design argument differed from earlier versions such as Sextus Empiricus (AD 160-210) Cicero (106-43 BC) because it appealed directly to the notion of purpose.

The scientific revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries rejected teleological explanation in terms of mechanical explanations. Nevertheless, Isaac Newton, the master of mechanical explanation, still had room for design. For Newton the mechanical operation of the universe was so intricate that it could not have been the product of design, it must have been the product of a cosmic designer.Mechanical explanations were not so successful in biology: ‘physics makes appeal only to efficient causes, whereas biology appeals to function and purpose’ (p. 109). William Paley’s (1740- 1805) Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity Collected from the Appearances of Nature (first published in 1802) made much use of biological examples. The book had much impact of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), he wrote ‘…Natural Theology gave me much delight’.

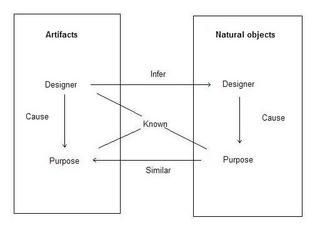

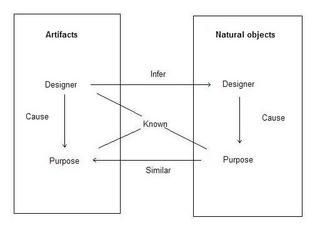

Paley’s argument rested on analogical reasoning, an important aspect of inductive reasoning. Dowe provides a helpful diagrammatic representation of Paley’s argument.

No comments:

Post a Comment