in a series of occasional posts I intend to provide a few pen portraits of some key British Calvinists. The list is not intended to be exhaustive. But may well include some or all (and others) of the list following this post. The list below is chronologically (by birth) and then alphabetical (by surname)

The term 'Calvinist' is not without problems. It is modified by a number of different prefixes (including hyper-, high-, low-, neo-, new-, classic-, moderate-) and has become associated worth the 5 points of TULIP. The points were first formulated at the Synod of Dordt - though the acronym TULIP dates back only to the early twentieth century. Those included in the list may well have modified their Calvinism with one of the prefixes, I have been inclusive rather than exclusive in including them.

For each one I hope to include why they are important, their key works, some quotes and what others may have said about them. This may well be adapted as the series progresses.

Hugh Latimer (1487-1555)

Miles Coverdale (1488-1569)

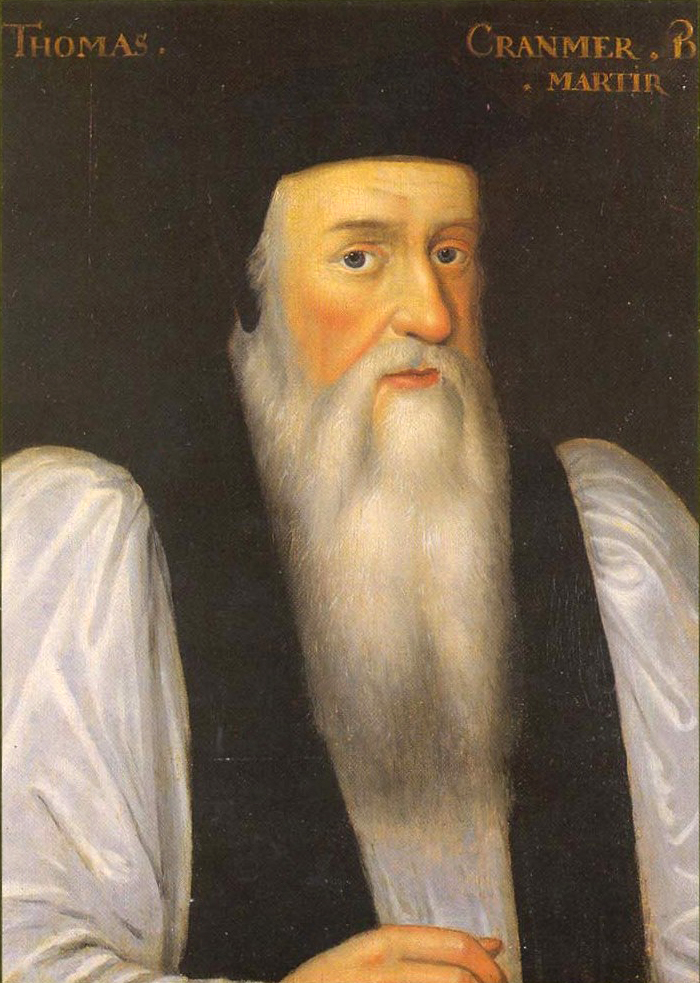

Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

John Hooper (c.1495-1555)

Nicholas Ridley (1500-1555)

Matthew Parker (1504-1575)

John Bradford (1510-1555)

George Wishart (1513-1546)

John Knox (1514-1572)

Edmund Grindal (1519-1583)

William Whittingham (1524-1579)

Thomas Cartwright (1535-1603)

Lawrence Chaderton (1536-1640)

Edward Dering (c.1540-1576)

John Field (1545-1588)

Walter Travers (c. 1548–1635)

John Rainolds (1549-1607)

Henry Barrowe (c 1550-1593)

John Greenwood (c. 1550-1593)

Robert Browne (1550-1633)

William Perkins (1558-1602)

Paul Baynes (c.1560-1617)

Henry Jacob (1563-1624)

Arthur Hildersham (1563-1632)

John Forbes (1568 -1634)

Thomas Gataker (1574-1654)

Joseph Hall (1574-1656)

William Ames (1576-1633)

John Davenant (1576-1641)

Richard Sibbes (1577-1635)

William Twisse (1578-1646)

William Gouge (1578-1653)

James Ussher (1581-1656)

John Ball (1585-1640)

Joseph Mede (1586-1638)

John Preston (1587-1628)

John Forbes (1593-1644)

John Spilsbury (c. 1593-1668)

John Davenport (1597-1670)

Jeremiah Burroughes (1599-1646)

Edward Reynolds (1599-1676)

Hanserd Knollys (1599-1691)

Tobias Crisp (1600-1643)

Samuel Rutherford (1600-1661)

Edmund Calamy (1600-1666)

Thomas Goodwin (1600-1680)

John Trapp (1601-1669)

Joseph Caryl (1602-1673)

John Lightfoot (1602-1675)

Isaac Ambrose (1604-1662)

Samuel Bolton (1606-1654)

John Milton (1608-1674)

Thomas Brooks (1608-1680)

Thomas Adams (1612-1653)

Richard Baxter (1615-1691)

John Owen (1616-1683)

William Kiffin (1616-1701)

William Gurnall (1617-1679)

Thomas Manton (1620-1677)

Thomas Watson (c. 1620-1686)

David Clarkson (1622-1686)

Matthew Poole (1624-1679)

Edward Fisher (1627-1656)

Stephen Charnock (1628-1680)

John Bunyan (1628-1688)

John Flavel (1630-1691)

John Howe (1630-1705)

Isaac Chauncy (1632-1712)

Joseph Alleine (1634-1668)

Benjamin Keach (1640-1704)

Robert Traill (1642-1716)

Daniel Williams (1643-1716)

Joseph Hussey (1660-1726)

Matthew Henry (1662-1714)

John Skepp (1675-1721)

Anne Dutton (1692-1765)

John Gill (1697-1771)

John Brine (1703-1765)

Daniel Rowland (1713-1790)

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

Howell Harris (1714-1773)

William Romaine (1714-1795)

Benjamin Beddome (1717-1795)

Anne Steele (1717-1778)

John Collett Ryland (1723-1792)

John Newton (1725-1807)

Robert Hall Sr (1728-1791)

Benjamin Francis (1734-1799)

Abraham Booth (1734-1806)

Thomas Haweis (1734-1820)

Caleb Evans (1737-1791)

Samuel Medley (1738-1799)

Augustus Toplady (1740-1778)

William Huntingdon (1745-1813)

John Rippon (1751-1825)

John Sutcliff (1752-1814)

Robert Hawker (1753-1827)

Charles Simeon (1759-1836)

William Carey (1761-1834)

John Sutcliff (1752-1814)

William Steadman (1764-1837)

Robert Haldane (1764-1842)

Joseph Kinghorn (1766-1832)

Samuel Pearce (1766-1799)

Christmas Evans (1766-1838)

Joshua Marshman (1768-1837)

William Ward (1769-1823)

Joseph Ivimey (1773-1834)

William Gadsby (1773-1844)

Alexander Carson (1776-1844)

John Stevens (1776-1847)

Andrew Fuller (1782-1815)

Christopher Anderson (1782-1852)

Joseph Irons (1785-1852)

William Nunn (1786-1840)

Andrew Reed (1787-1862)

John Kershaw (1792-1870)

William Rushton (1796-1838)

J. C. Philpot (1802-1869)

William Tiptaft (1803-1864)

William Knibb (1803-1845)

James Wells (1803-1872)

William McKerrow (1803-1878)

William Cunningham (1805-1861)

J C Ryle (1816-1900)

Alexander Maclaren (1826-1910)

C H Spurgeon (1834-1892)

Henry Wace (1836-1924)

James Kidwell Popham (1847-1937)

Thomas Houghton (1859-1951)

William Sykes (1861-1930)

John R. Mackay (1865-1939)

Donald Maclean (1869-1943)

Henry Atherton (1875-

Arthur W. Pink (1886-1952)

Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1981)

G N M Collins (1901-1989)

E F Kevan (1903-1965)

R Tudor Jones (1921-1998)

E. L. Hebden Taylor (1925-2006)

Alphabetical list of some British Calvinists

Thomas Adams (1612-1653)

Joseph Alleine (1634-1668)

Isaac Ambrose (1604-1662)

William Ames (1576-1633)

Christopher Anderson (1782-1852)

Henry Atherton (1875-

John Ball (1585-1640)

Henry Barrowe (c 1550-1593)

Richard Baxter (1615-1691)

Paul Baynes (1560-1617)

Benjamin Beddome (1717-1795)

Samuel Bolton (1606-1654)

Abraham Booth (1734-1806)

John Bradford (1510-1555)

John Brine (1703-1765)

Thomas Brooks (1608-1680)

Robert Browne (1550-1633)

John Bunyan (1628-1688)

Jeremiah Burroughes (1599-1646)

Edmund Calamy (1600-1666)

William Carey (1761-1834)

Alexander Carson (1776-1844)

Thomas Cartwright (1535-1603)

Joseph Caryl (1602-1673)

Lawrence Chaderton (1536-1640)

Stephen Charnock (1628-1680)

Isaac Chauncy (1632-1712)

David Clarkson (1622-1686)

G. N. M. Collins (1901-1989)

Myles Coverdale (1488-1569)

Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

Tobias Crisp (1600-1643)

William Cunningham (1805-1861)

John Davenant (1576-1641)

John Davenport (1597-1670)

Edward Dering (c.1540-1576)

Anne Dutton (1692-1765)

Caleb Evans (1737-1791)

Christmas Evans (1766-1838)

John Field (1545-1588)

Edward Fisher (1627-1656)

John Forbes (1568 -1634)

John Flavel (1630-1691)

Andrew Fuller (1782-1815)

William Gadsby (1773-1844)

Thomas Gataker (1574-1654)

John Gill (1697-1771)

Thomas Goodwin (1600-1680)

William Gouge (1578-1653)

John Greenwood (c. 1550-1593)

Edmund Grindal (1519-1583)

William Gurnall (1617-1679)

Robert Haldane (1764-1842)

Joseph Hall (1574-1656)

Robert Hall Sr (1728-1791)

Howell Harris (1714-1773)

Robert Hawker (1753-1827)

Thomas Haweis (1734-1820)

E. L. Hebden Taylor (1925-2006)

Matthew Henry (1662-1714)

Arthur Hildersham (1563-1632)

John Hooper (c.1495-1555)

Thomas Houghton (1859-1951)

John Howe (1630-1705)

William Huntingdon (1745-1813)

Joseph Hussey (1660-1726)

Joseph Irons (1785-1852)

Joseph Ivimey (1773-1834)

Henry Jacob (1563-1624)

R Tudor Jones (1921-1998)

John Kershaw (1792-1870)

William Kiffin (1616-1701)

Joseph Kinghorn (1766-1832)

Benjamin Keach (1640-1704)

E. F. Kevan (1903-1965)

Hanserd Knollys (1599-1691)

William Knibb (1803-1845)

John Knox (1514-1572)

Hugh Latimer (1487-1555)

John Lightfoot (1602-1675)

Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1981)

John R. Mackay (1865-1939)

Donald Maclean (1869-1943)

Alexander Maclaren (1826-1910)

Thomas Manton (1620-1677)

Joshua Marshman (1768-1837)

William McKerrow (1803-1878)

Joseph Mede (1586-1638)

Samuel Medley (1738-1799)

John Milton (1608-1674)

John Newton (1725-1807)

William Nunn (1786-1840)

John Owen (1616-1683)

Matthew Parker (1504-1575)

Samuel Pearce (1766-1799)

William Perkins (1558-1602)

J. C. Philpot (1802-1869)

Arthur Pink (1886-1952)

Matthew Poole (1624-1679)

James Kidwell Popham (1847-1937)

John Preston (1587-1628)

John Rainolds (1549-1607)

Andrew Reed (1787-1862)

Edward Reynolds (1599-1676)

Nicholas Ridley (1550-1555)

John Rippon (1751-1825)

William Romaine (1714-1795)

Daniel Rowland (1713-1790)

William Rushton (1796-1838)

Samuel Rutherford (1600-1661)

John Collette Ryland (1723-1792)

J. C. Ryle (1816-1900)

John Sutcliff (1752-1814)

Richard Sibbes (1577-1635)

Charles Simeon (1759-1836)

John Skepp (1675-1721)

John Spilsbury (c. 1593-1668)

C. H. Spurgeon (1834-1892)

William Steadman (1764-1837)

Anne Steele (1717-1778)

John Stevens (1776-1847)

John Sutcliff (1752-1814)

William Sykes (1861-1930)

Walter Travers (c. 1548–1635)

William Tiptaft (1803-1864)

Augustus Toplady (1740-1778)

Robert Traill (1642-1716)

John Trapp (1601-1669)

William Twisse (1578-1646)

James Ussher (1581-1656)

Henry Wace (1836-1924)

William Ward (1769-1823)

Thomas Watson (1620-1686)

James Wells (1803-1872)

William Whittingham (1524-1579)

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

Daniel Williams (1643-1716)

George Wishart (1513-1546)